This year’s conference is on the theme of stained glass revivals, and will look at three eras in which there was either a period of new stained glass being set up in churches after a period without, or where stained glass took a new artistic and stylistic turn. We have an excellent panel of speakers, each of them expert in their particular field and period. They will speak in pairs to address three periods when revival has happened: the early seventeenth century, the long nineteenth century, and the middle period of the twentieth century, either side of the Second World War. Abstracts of the papers are set out below. The day will explore the range of similarities in these eras as well as the difference between them, looking at style, technique and meaning. It will be a particularly colourful day.

Mark Kirby: The first revival & the conundrum of Calvinist stained glass

The English Reformation saw extensive but not total destruction of stained glass; pragmatism required windows of some sort to remain in place. However, the Church’s “Homily Against Peril of Idolatry” prohibited the creation of new figurative stained glass, and what little new stained glass there was was mostly armorial. Nevertheless, a rebirth of stained glass took place from the turn of the seventeenth century. This paper examines how that rebirth came about and how it came to a crashing end with the outbreak of the Civil War.

Associated with Archbishop William Laud in much historical writing, this period saw the surprising phenomenon of figurative stained glass being commissioned by churchmen from the Reformed wing of the Church of England, principally in London and Oxford. Nearly all of the London glass was destroyed in the 1640s, but much of what was made for Oxford college chapels remains.

Robert Walker: Two Gentlemen of Pomona and their early 17th Century stained glass in Herefordshire

The paper will examine glazing schemes by two prominent Herefordshire gentry – Fitzwilliam Coningsby (1596–1666) and Viscount John Scudamore (1601–71). They were contemporaries and rivals, but both apparently leaned towards Laudian ideas.

The Coningsby chapel at Hampton Court held some painted glass arms of 1614 installed by Thomas Coningsby (1550– 1625), father of Fitzwilliam, and a small, dated Deposition of 1629 by Abraham van Linge which was probably commissioned by Fitzwilliam. It is now in the V&A. Its inscription betrays the ceremonialist, Beauty-of-Holiness inclinations of the purchaser. It is inscribed, “The truth here of is historicall divine and not superstissious”.

John Scudamore is associated with three churches – Sellack, Abbey Dore and Much Marcle. His glass is instantly recognisable as being not medieval – mainly because of its colours and draughtsmanship – but is conceived, composed and made in an entirely medieval fashion. A later alteration of the Abbey Dore glass brings the Renaissance into collision with the Gothic in the form of an Ascension image.

This paper will examine the composition of the windows and their sources of inspiration. It will look to contemporary glass and make some comparisons.

Jim Cheshire: What does Victorian stained glass mean?

This paper will explore the iconography of Victorian Stained Glass. While art historical narratives and cataloguing have gone a long way towards identifying the extant corpus of Victorian stained-glass windows, relatively few scholars have concentrated on what patrons and artists sought to communicate through their windows. This paper will suggest that while some modes of representation were deliberately revived from the Middle Ages, Victorian stained glass was often unique in the way that it used religious imagery. Approaches varied enormously. The meaning of some windows relied on relational semantics: images in windows worked as part of a wider iconographical scheme throughout the building. Large windows might contain their own relational logic through creating relationships between images and texts. As stained glass became more popular, middle-class patrons often commissioned individual windows that sought to convey more personal messages: here iconography was deployed to articulate a significant event in life of the donor. Innovations such as the integration of portraiture made some of these windows highly idiosyncratic. These two approaches to stained glass, one seeking to contribute to a wider scheme and the other seeking to articulate personal narratives often worked in opposing directions, which sometimes led to conflict. The approach to iconography was often dictated by the donor but the attitude of the glass painter could also be a key factor: the style of the window and the technical approach of the studio had a significant impact on the nature of the imagery.

Jasmine Allen: In search of artistic freedom: British stained glass in the long 19th century

The 19th century witnessed one of the most productive and inventive periods in the history of stained glass. For the first time since the Middle Ages, stained glass flourished once again as a major art form in both religious and secular settings across Europe, and beyond.

In this period the art of stained glass underwent a number of stylistic transitions from spectacular paintings on glass to archaeological windows of the gothic revival to the more inventive richly coloured and densely leaded Arts and Crafts productions and, even early expressions of modern abstraction.

This talk will provide a brief overview to some of the main developments in Britain in this period between 1840 and 1915, looking especially at how developments in glass material and technology shaped stained glass design and making, how artists exploited their translucent glass material to achieve new effects, and changes in approaches to studio practice. It will argue that it was in this period that the foundations were laid for modern stained glass.

Martin Crampin: Reaching beyond the conventional: British ecclesiastical stained glass 1930–1980

Stained glass studios that produced most of the stained glass windows for British churches adapted their work to changing tastes in the middle years of the twentieth century. While innovation can clearly be seen among better-known artists that produced high-profile commissions from the 1950s, many stained glass designers had already set aside the conventions of the Gothic Revival that continued to dominate ecclesiastical stained glass into the 1920s.

Responses to the need for modern stained glass included a retreat from naturalism and the adoption of different medievalisms. A variety of approaches were common, even in different windows by the same designers. Some windows were designed to admit much more light into churches, while others made use of strong colour and thick lead lines. At the same time there was also a degree of resistance among certain stained glass designers and patrons to innovation and abstraction.

Modernist buildings provided new architectural contexts that allowed for the introduction of dalle de verre, which offered additional possibilities for artists from the 1960s together with other new techniques for adding colour, design and texture to architectural stained glass.

Diana Coulter: ‘Allelujahs of many coloured glass’: a post-war revival or new directions?

Reconstruction after the Blitz created an unprecedented opportunity to think afresh about church buildings and their stained glass windows. The story should not be about Coventry only – other cities suffered as much damage. In this paper Diana Coulter, co-author of “Keith New: British modernist in stained glass”, will look at a thirty-year period in which she also covers Manchester and Plymouth. She will address how ecclesiastical authorities responded both to the effects of the Blitz and to the imperative to cater for a growing population. Aspects of new approaches to design will be considered alongside technical innovation and the diversity of commissions. Questions will be raised about how much we value post-war glass today and whether the legacy is flourishing particularly in light of the recent inclusion of stained glass window making on the Red List of Endangered Heritage Crafts.

Attendance fees:

The costs for those attending in person (including refreshments, lunch and a glass of wine afterwards):

£70 for members of the Ecclesiological Society and their guests

£80 for non members; £40 for students.

The costs for those attending on-line:

£40 for members of the Ecclesiological Society and their guests

£50 for non members; £20 for students

All bookings should be made through the Ecclesiological Society’s Eventbrite page here

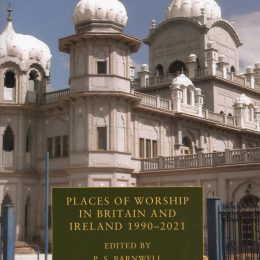

Places of Worship in Britain and Ireland, 1990–2021

Places of Worship in Britain and Ireland, 1990–2021 Competing Churches and Chapels, 1829–1939

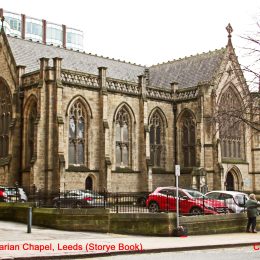

Competing Churches and Chapels, 1829–1939 Geoff Brandwood Memorial Lecture: Historic building mythbusting – investigating mediaeval parish churches

Geoff Brandwood Memorial Lecture: Historic building mythbusting – investigating mediaeval parish churches Study Day: St Cadoc, Llancarfan and St Illtud, Llantwit Major, Wales

Study Day: St Cadoc, Llancarfan and St Illtud, Llantwit Major, WalesHave you got a story of general interest about churches?

Want to be the first to hear our news? Sign up below and we’ll notify you by email when we add a new article.